Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 4

Inclusive Climate Action through Charrette-Based Consultation

This post is the fourth of five in this series written by Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF) policy clinic students. This series is intended as an introduction to the importance of, and potential for, effective and inclusive public engagement in municipal land-use planning, place-making and climate action governance. Cities are a uniquely-situated level of government in their ability to facilitate public engagement and experiment with different approaches to conducting community consultations. This series highlights a charrette design approach, which has seen high levels of success in a variety of municipal settings.

(4 May 2021) By Katie Pfaff

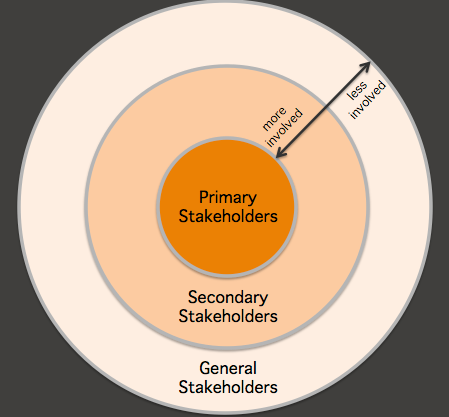

The charrette process is of specific use to building a climate plan, in its ability to identify and engage groups who are directly affected by policy decisions and yet often unrepresented in the decision-making process.

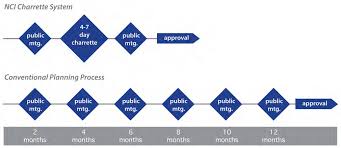

As discussed in Part 1 of this blog series, s. 17(15)(d) of the Ontario Planning Act dictates that a city council is only required to provide one “public meeting” as part of their planning efforts. While one is better than none, if there is no meaningful consultation, such activity fails to serve a useful purpose; especially when council is making decisions affecting a group to which no council members belong nor bring shared experiences. A charrette process fulfills this gap, specifically in relation to the climate crisis and its disproportionate effect on marginalized groups as discussed in Part 3.

A charrette process allows for meaningful engagement because the solutions are created by the groups most affected by the issue. In the context of climate policy, this includes those disproportionately affected by the climate crisis.

A charrette process is considered the gold standard of community engagement because it allows community stakeholders to be involved in municipal climate decision making from the inception of an issue, ie at the identification stage. Rather than top-down initiatives, a charrette process has the potential to create authentic, place-based initiatives that reflect the needs of the communities the initiative or policy is intended to serve.

However, such a process is not without its challenges. For a charrette process to be successful, it requires community buy-in from diverse groups. As discussed in Part 2, while the organization of logistics is important, a charrette process must also prioritize building rapport and trust with groups that have historically had negative experiences interacting with oppressive systems that serve to the benefit of those in positions of privilege. This may be the case in particular for members of Black and Indigenous communities.

Environmental racism not only exists but is pervasive. We all experience the climate crisis, but we do not all experience it equally. Conversations around environmental sustainability fail to address the root problems of colonialism and capitalism that perpetuate environmental racism, and as such, community engagement is a necessity in ensuring that climate mitigation is not only sustainable but socially equitable.

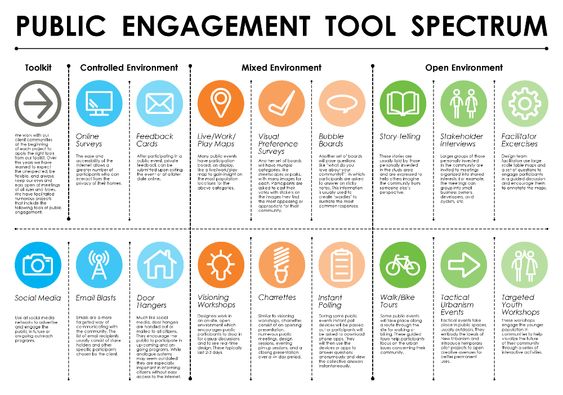

A charrette involves breaking down barriers and being open to listen, learn, and be challenged by the lived experience of those directly affected by policy decisions. It also situates those with lived experience as the experts of the problem at hand and those who hold the solutions. In order to achieve this, the charrette process promotes a bidirectional relationship of proponents and public sector experts informing and educating the public, and in turn, incorporating the values of the public into decision-making. This ultimately improves the quality of decisions, fosters trust in institutions and reduces conflict. To achieve this, a charrette should adopt an engagement framework that not only sets principles of engagement, but one which also commits to diversity, engagement of underrepresented groups, and building staff capacity in these areas.

Such a process takes time and members of diverse groups may already experience different levels of systemic strain that inhibit them from participating in additional activities. For example, women with children may experience the second shift of caregiving responsibilities outside of working hours, making it difficult to take part in other initiatives. For other key groups, language is the barrier and translation into English or French is required to facilitate their participation.

Members of other groups may have grown weary of their voices and activism being ignored for so long that it is difficult to find the energy to trust a system that never seems to change. A properly-designed charrette process challenges these preconceptions; for meaningful engagement to occur, accommodations must be made to meet community stakeholders where they are at. Ways to do this include determining the timing and setting of the meeting. Is the time reasonable for the community members the charrette process hopes to engage? Is the building itself accessible? Is childcare available? Will participants be compensated for their time? Due to COVID-19 and many meetings still being conducted remotely, are members of included communities able to call in? If meetings are conducted in person, is the location walkable or easily accessible by bicycle or transit?

Within this collaborative space, the ideas of these community members can be actively and thoughtfully included as the foundation for any climate intervention. A charrette process recognizes the inherent strength, dignity, and expertise of community stakeholders, which is why it lends itself so perfectly to putting diversity, equity, and inclusion in practice.

Katie Pfaff is a rising 3L Windsor Law MSW/JD student, and student member of the Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum policy clinic. We thank Jim Tischler, Visiting Fellow of the Windsor Law Centre for Cities, for acting as consultant to this blogpost series.

Climate Blog series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 5

Concluding Thoughts: Lessons for Cities and Climate Action Planning Processes This post is the last of five in this series…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 3

Public Engagement and Charrette Processes in Climate Action This post is the third of five in this series written by…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 2

An Introduction to The Charrette Process This post is the second of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Municipal Public Engagement, Part 1

The Current Framework on Municipal Public Consultations in Ontario This post is the first of five in a new series…