Climate Blog series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 5

Concluding Thoughts: Lessons for Cities and Climate Action Planning Processes

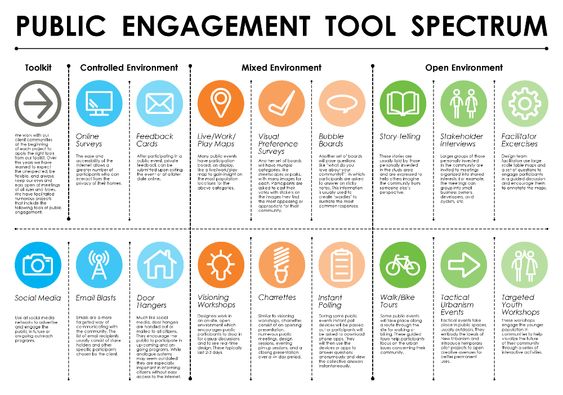

This post is the last of five in this series written by Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF) policy clinic students. This series is intended as an introduction to the importance of, and potential for, effective and inclusive public engagement in municipal land-use planning, place-making and climate action governance. Cities are a uniquely-situated level of government in their ability to facilitate public engagement and experiment with different approaches to conducting community consultations. This series highlights a charrette design approach, which has seen high levels of success in a variety of municipal settings.

(14 May 2021) By Narmada Gunawardana

This blog post concludes our short series on public engagement in municipal climate action, with a focus on charrettes as one potential model.

We hope the series has provided some insight on how a charrette process can improve public consultation. Previous posts in this series discussed current public consultation in municipalities, how a charrette process works, the need for an inclusive process in climate action at the community level, and how charrette processes work to include diverse groups.

This last post revisits several key points from the series and summarizes some relevant best practices.

1. Beyond design or land use planning, the charrette process has potential for a range of community planning issues. (Charrettes have even been used to help create the process for future consultations.)

2. Like any other form of public consultation, a municipally-led charrette process needs to bring in a range of stakeholders, including broad community representation as well as the necessary experts (planners, architects, transportation engineers, landscape architects, etc). These stakeholders also should be included as early as possible in the process in order to optimize the potential for meaningful input and avoid wasting time and money.

3. In order to ensure effective charrettes, municipalities may wish to consider outsourcing some or all of the process. Hiring third party consultants who specialize in this work can ensure the process is done effectively and timely. Community groups or stakeholder organizations may also have a collaborative role to play in facilitating all or part of the charrette and/or participation.

4. The charrette process needs to be created with inclusivity in mind, with the understanding that stakeholder participants have busy personal and work lives. The need for in-person attendance can thus create barriers for those who do not have access to transportation, live far from the designated site, or have childcare responsibilities. Compensation for participation may be appropriate in some cases.

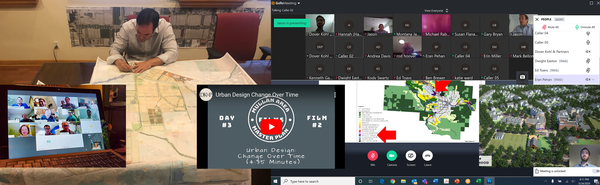

5. The move to remote working due to COVID-19 has also shown us the power of technology in creating increased access to participation. While the World Bank recommends that charrettes be held on-site, the option to participate remotely may be a good and inclusive part of the charrette process. In fact, a virtual charrette has the potential to attract even more people into the process. A Michigan State University study found that virtual charrettes and related virtual planning events attract more people than the usual in-person public hearings and meetings. It was noted in the study that more than 50% of adults will never attend a public meeting during their lifetime due to the time and interest constraints and so virtual hearings can help decrease these barriers. Municipalities may therefore wish to consider the feasibility of conducting some charrette processes virtually, even after the COVID-19 crisis.

6. As municipalities become more engaged in – and lead – climate action, they are increasingly called on to ensure that council decisions align with long-term climate change adaption and mitigation goals. The involvement of a diversity of stakeholders in the climate action planning process will help to ensure that the various dimensions of climate action are brought to the table. These include an inclusivity lens that looks at the adverse climate change impacts on disadvantaged communities, perspectives from low-income communities, impacts on the natural environment and its species, and more. A charrette process offers one way to do this.

7. Charrette processes are more expensive and time-consuming to implement than many other forms of consultation. They may not be feasible in every circumstance and for every municipality. However, given the need for an overarching climate lens to be brought to all municipal decision-making at this time, a city’s climate planning might be one place where a charrette process is particularly justified.

8. Charrette processes may also be an optimal way to ensure that the climate lens is brought onto all planning decisions made by a municipality. This can be done by ensuring that a climate change expert is involved as a stakeholder in all charrette processes for development projects, for example.

9. Overall, a charrette-informed process is a promising way forward in community climate planning. The process allows for the inclusion of a large number of stakeholders that will bring broad and diverse perspectives into the process from the beginning. This will in turn help ensure that perspectives and concerns are shared in the beginning of the planning process rather than in the implementation stages. And including so many experts, community members and stakeholder organizations from the start will help to build buy-in and momentum for the plan across the community.

Climate change is the single most pressing issue of our time. A whole-of-community approach must be taken.

Narmada Gunawardana is a graduating Windsor Law student, and student member of the Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum policy clinic. We thank Jim Tischler, Visiting Fellow of the Windsor Law Centre for Cities, for acting as consultant to this blogpost series.

Main image credit: https://www.pinterest.ca/urbangranola/_saved/

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 4

Inclusive Climate Action through Charrette-Based Consultation This post is the fourth of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 3

Public Engagement and Charrette Processes in Climate Action This post is the third of five in this series written by…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 2

An Introduction to The Charrette Process This post is the second of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Municipal Public Engagement, Part 1

The Current Framework on Municipal Public Consultations in Ontario This post is the first of five in a new series…