Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 3

Public Engagement and Charrette Processes in Climate Action

This post is the third of five in this series written by Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF) policy clinic students. This series is intended as an introduction to the importance of, and potential for, effective and inclusive public engagement in municipal land-use planning, place-making and climate action governance. Cities are a uniquely-situated level of government in their ability to facilitate public engagement and experiment with different approaches of conducting community consultations. This series highlights a Charrette design approach, which has seen high levels of success in a variety of municipal settings.

(30 April 2021) By Joy Wahba

Despite overwhelming scientific consensus on the impacts of climate change and the urgent need for transformation of energy use, municipal climate action remains to some extent a political and divisive undertaking. Even as communities are beginning to witness the effects of climate change locally, key stakeholders at the local level disagree about the level of action that climate change requires, what needs to change, and how to change it. Further, vulnerable communities often disproportionally feel the effects of climate change and yet are often left out of participation in decision-making (see Part 4 of this series for more on this topic). What is abundantly clear is that all stakeholders are responsible for mitigating the risk of climate change and need to be a part of designing and implementing climate plans. Further, local governments can only lead so much in terms of environmental protection and energy regulation without the support and partnership of citizens and the private sector.

So, how can municipalities design effective climate action for their communities despite diverse opinions and engagement from key stakeholder groups? And how can municipalities ensure that the implementation of their community energy and climate action plans involves robust support and collaboration by key stakeholders such as private sector?

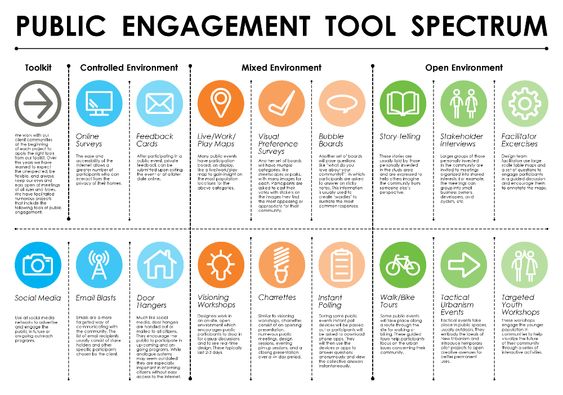

As introduced in Part 2, the charrette process for community engagement provides a space for communities to work through divisive issues and develop plans. It is a process which is about community problem-solving, promoting joint ownership and diffusing confrontation. Typically, the charrette process has been employed by cities in the context of land-use planning wherein residents, developers, community organisations, businesses and city officials co-design plans for their communities. For example, communities may work through the design of a local park, or a housing cooperative using a charrette process.

However, municipalities can also benefit from the use of a charrette process in the context of climate action. Given the often-divisive nature of local action on climate change, and the need for robust collaboration from even the most obstinate stakeholders, a charrette process can assist municipalities to confront the most pressing barriers they face creating space for effective community engagement on climate action. There are several dimensions to effective action on climate change at the local level. Burch describes four types of barriers: structural/operational, regulatory/legislative, cultural/behavioural, and contextual factors. She underscores the need for local government to overcome these barriers. The charrette process is a key way that enables stakeholders to transform obstacles such as an organizational culture of combativeness and mutual disrespect into a culture of collaboration or innovation.

Not only can a charrette transform attitudes and spaces for collaboration, Khirfan writes that a charrette design approach helps to build awareness, capacity and agency on climate change. Further, it builds support for local planning and decision-making. Municipalities must recognize the need for community and stakeholder engagement to achieve the ambitious local/regional/global climate change mitigation targets that will enable a climate future. A report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change underscores the role of private sector to implement ambitious action directed at limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. A charrette process can assist municipalities to engage with stakeholders like the private sector to build a sense of joint ownership and resolve conflict and misunderstanding. It can enable local government to overcome several types of barriers to develop effective, robust, and collaborative strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

This is possible as a result of the fundamental elements of a charrette process as outlined in Placemaking as an Economic Development Tool: A Placemaking Guidebook. For example, by facilitating collaboration, charrettes produce better plans with improved planning outcomes that are widely supported. By bringing relevant stakeholders that come from different backgrounds, professions together at the same time, a charrette process can enable the group to root out initial issues as they arise, creating efficiency and resulting in development planning rather than a plan for development. As mentioned in Part 2, time compression can increase creativity, reduce unnecessary side tracks and improve decision-making. A compressed time period also helps to modify stakeholder perspectives and opinions. Finally, feedback loops in a charrette process build trust, facilitate understanding and ultimately build support for the outcomes.

Part 2 clearly stated the benefits of a charrette process to achieve meaningful, deep, and collaborative public engagement. As public engagement remains an enormous obstacle for municipal climate action, the charrette model offers an ideal method to overcome that barrier. We encourage municipalities to understand the scale and speed at which municipal climate action must occur to limit climate change. In so doing, they will begin to grasp the tremendous need for public and private sector engagement. Investing in engagement from these stakeholders will make the necessary ambitious goals possible.

Joy Wahba is a graduating Windsor Law student and member of the Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF) policy clinic. We thank Jim Tischler, Visiting Fellow of the Windsor Law Centre for Cities, for acting as consultant to this blogpost series.

Main image credit: Shutterstock (Montreal, 2019)

Climate Blog series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 5

Concluding Thoughts: Lessons for Cities and Climate Action Planning Processes This post is the last of five in this series…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 4

Inclusive Climate Action through Charrette-Based Consultation This post is the fourth of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 2

An Introduction to The Charrette Process This post is the second of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Municipal Public Engagement, Part 1

The Current Framework on Municipal Public Consultations in Ontario This post is the first of five in a new series…