Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 2

An Introduction to The Charrette Process

This post is the second of five in this series written by Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF) policy clinic students. This series is intended as an introduction to the importance of, and potential for, effective and inclusive public engagement in municipal land-use planning, place-making and climate action governance. Cities are a uniquely-situated level of government in their ability to facilitate public engagement and experiment with different approaches of conducting community consultations. This series highlights a Charrette design approach, which has seen high levels of success in a variety of municipal settings.

(27 April 2021) By Klaudia Grabkowska and Valerie Tan

This second post in the series explores one response to the public consultation conundrum that communities face – the charrette model for public engagement. Much of the following is based on publicly available material from the US-based National Charrette Institute (NCI), a non-profit which provides resources and training to facilitate the creation of healthy community plans.

About the Charrette Process

According to the NCI, a charrette can be described as an intense, organized public participation spanning multiple days and involving a broad range of public and private stakeholders, facilitators, and design and development professionals. The charrette engages individuals by facilitating a hands-on approach to place-making. A professional team, including experts in land use planning, engineering, finance, architecture and more, engages with community members where stakeholder feedback is reviewed continuously throughout the process. The professional team is responsible for transforming the community’s vision and local knowledge of an area into a feasible design and implementation strategy, which incorporates the diverse perspectives of stakeholders through information sharing, listening, and deliberation, the NCI explains.

The Goals and Advantages of the Charrette Process

Meaningful Public Engagement

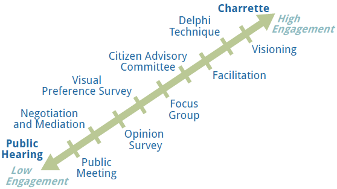

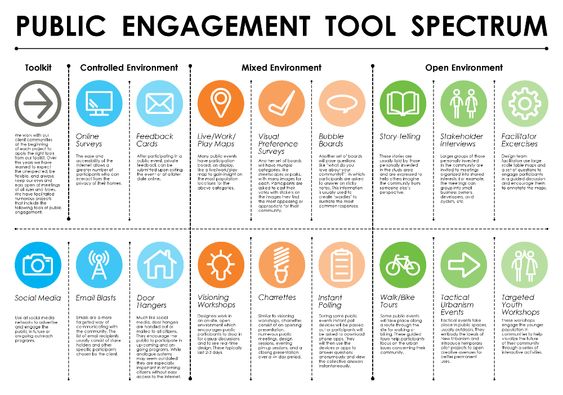

Some suggest that there is a hierarchy of public engagement techniques (Figure 1). The charrette sits at the top of the hierarchy and provides the highest level of public engagement because it encompasses virtually all other forms and techniques jointly. On the other hand, public hearings – which continue to be commonly relied on in many development projects – are located on the complete opposite end of the spectrum.

As per section 17 of the Ontario Planning Act, the public must be informed in a public hearing about proposed plans and members of the public given an opportunity to make representations in respect of the plan. The public hearing constitutes one of the limited avenues of public engagement for many members of the public because it is the minimum standard required by law. However, it is available to a municipality to utilize more robust consultation tools which include more intensive, detailed and ongoing consultations within the scope of the law. Better approaches to meaningful public engagement which also fulfill the requirements under the Planning Act can and should be implemented.

One of the biggest benefits of a charrette is that it promotes joint ownership of solutions to problems and ways to seize opportunities. The potential for traditional confrontation between residents, developers, and local government officials is reduced by actively involving stakeholders in the planning or physical design of the community. Members of the public have a lot to offer in the form of ideas, opinions, and concerns about the places they occupy. Their input can influence the success of a project and the extent to which it benefits those it was ultimately meant to serve.

Image credit: Figure by the MSU Land Policy Institute and Brad Neumann, Michigan State University Extension, 2015.

Time Compression

The Planning Act in section 17(15(d)) requires that at a minimum, one public meeting is held in relation to land use proposals. This requirement does not incentivize communities and municipal councils to engage in an extensive public engagement process which may be spaced out over weeks or months. A charette, on the other hand, compresses a robust public consultation process into a matter of a day or days. Time compression is important to the success of the charette process. This is because by bringing together various stakeholders, experts, and facilitators for several consecutive days, the charrette “encourages creative problem solving, accelerates decision making, and reduces nonconstructive negotiation tactics” (Lennertz and Lutzenhiser 2003 at p. 5). Furthermore, this shorter timeline keeps the vision and importance of the impacts of the proposed plan fresh in the minds of the community members.

A successful charrette process will be cost- and time-effective and expedite the development and adoption of the planning strategy forward. According to the NCI, “Rather than chipping away at a problem one meeting at a time over a period of weeks or months, the NCI charrette approach brings specialists together for an uninterrupted work session to break through to a creative solution. What typically takes months, is accomplished in a fraction of the time.” This process is highly efficient and produces design plans which can quickly proceed onto the adoption phase and move into development shortly thereafter.

The Example of Ontario Place – Toronto, Ontario

One of the most recent examples of a charrette in Toronto took place on March 30, 2019 at the Toronto Central YMCA. This design charrette was held by the Toronto Society of Architects (TSA) with a focus on the future vision of Ontario Place. This charrette exemplifies especially well the goals a charrette is meant to achieve. Specifically, by incorporating participants from both the public alongside various industry experts, it allowed for meaningful public involvement in the design and planning process.

Maria Denegri, Chair of the TSA, stated that “Perhaps the most important lesson we learnt during the charrette is how engaged and invested both the professional design community and the general public are about the future of this unique site.”

Denegri further adds that, “Ontario Place is a cultural asset that belongs to all Ontarians and public consultation and engagement need to play a leading role in setting the direction for its future and ensuring it is representative and reflective of our province’s diversity, ideals and dreams.” This is a reminder of the value of the charrette. There is a strong need to actively include the public in decisions which directly affect spaces in the community, and the charrette process wholly allows for this. Further, this design charrette significantly compressed the timeframe for the project. In particular, the same progress which would typically take months was accomplished over the course of a full day.

A Step-by-Step Process

Consider the following three-phase process created by the NCI Charrette System™:

Step 1: Preparation: Prepare all parties involved in the project using the following tools:

- Project Assessment and Organization: establishing a project start-up meeting, a project roadmap, and the scope, budget and schedule.

- Stakeholder Research and Involvement: conduct stakeholder analysis and interviews.

- Base Data Research and Analysis: conduct a SWOT analysis

- Charrette Logistics: consider the location of the charrette to take place and assemble a team.

Step 2: Charrette: The charrette team will present a community vision and engage with stakeholders and gather input through a series of feedback loops and meetings.

Step 3: Implementation: Following up from the charrette, the project team will review and finalize the product outcome and can conduct a final feedback meeting .

A successfully planned charrette will ideally achieve consensus in community support for feasible plans. In preparing to carry out the charrette, a planning team should determine the purpose and agenda of the public meeting, seek to establish relationships with all participants prior to the meeting, consider the logistics (such as time and meeting space) and planning for follow-up communications post-event regarding the status of the project/plan.

The charrette is ideal for implementing at a neighbourhood scale or specific development site applications which can form part of a larger regional or community-wide planning process, including climate adaptation or mitigation planning. Take for example, the Green Waterfront Design Charrette completed in Vancouver, British Columbia which explored how changes in land use planning including green infrastructure development could support community resilience to sea level rise and protecting and restoring coastal ecosystems.

The NCI suggests using social media to spread awareness and to put out a call for volunteers in the community to seek out community members who are invested in public engagement. In order to ensure that community member participants are truly representative of the city or neighbourhood affected, more targetted calls are probably also advisable.

Klaudia Grabkowska and Valerie Tan are Windsor Law students and student members of the Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum policy clinic. We thank Jim Tischler, Visiting Fellow of the Windsor Law Centre for Cities, for acting as consultant to this blogpost series.

Main image credit: College of Environment + Design, University of Georgia

Climate Blog series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 5

Concluding Thoughts: Lessons for Cities and Climate Action Planning Processes This post is the last of five in this series…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 4

Inclusive Climate Action through Charrette-Based Consultation This post is the fourth of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 3

Public Engagement and Charrette Processes in Climate Action This post is the third of five in this series written by…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Municipal Public Engagement, Part 1

The Current Framework on Municipal Public Consultations in Ontario This post is the first of five in a new series…