Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Municipal Public Engagement, Part 1

The Current Framework on Municipal Public Consultations in Ontario

This post is the first of five in a new series “Steps to Public Engagement”, written by Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF) policy clinic students. This series is intended as an introduction to the importance of, and potential for, effective and inclusive public engagement in municipal land-use planning, place-making and climate action governance. Cities are a uniquely-situated level of government in their ability to facilitate public engagement and experiment with different approaches of conducting community consultations. This series highlights a Charrette design approach, which has seen high levels of success in a variety of municipal settings.

(22 April 2021) By Mallory Allan

In this first post, we discuss the legal and policy landscape for municipal public consultation in Ontario, and the low level of public engagement in most municipalities.

Much of the land use planning process in Ontario is regulated through the provisions of the Planning Act. The Planning Act provides for public participation in a number of ways, including the rights of residents to be notified about planning proposals, to give their views to City Council and to appeal decisions to the Local Planning Appeals Tribunal (LPAT). Public consultation is mandated for a variety of planning processes from official plan adoption to subdivision applications. The Municipal Act also provides for a limited number of circumstances where public consultation is required. In most cases where legislation mandates a public consultation by the municipality, this comes in the form of a requirement to hold “a public meeting”.

However, while one public meeting may be sufficient to satisfy legislative requirements, public consultation and public engagement are two entirely different concepts. Meaningful public participation means that members of the public who want to participate actively in public consultations have an opportunity to do so. It means that they have access to the information they need to take part in an informed way, and that their perspectives inform and influence decisions. Citizens of a community are ‘engaged’ when they are not only consulted, but when they take an active role in municipal decision making. The public meeting requirement should therefore be seen more as a floor, or minimum requirement, than a ceiling.

Beyond this, there are opportunities for meaningful resident input into municipal decision-making even when not mandated by law. Developing municipal climate policy would be one such example. As it stands, Canadian municipalities have struggled to generate meaningful public participation and engagement, even when public consultations are held in accordance with legislative requirements.

Canadian municipalities are facing what has been referred to by community development scholars as a ‘public engagement conundrum.’ According to a 2017 survey done by IPSOS, a global leader in market research, most Canadians are not engaging with public consultations conducted on behalf of their municipality. Municipalities are investing funds into holding public consultations with very little participation from their residents in return.

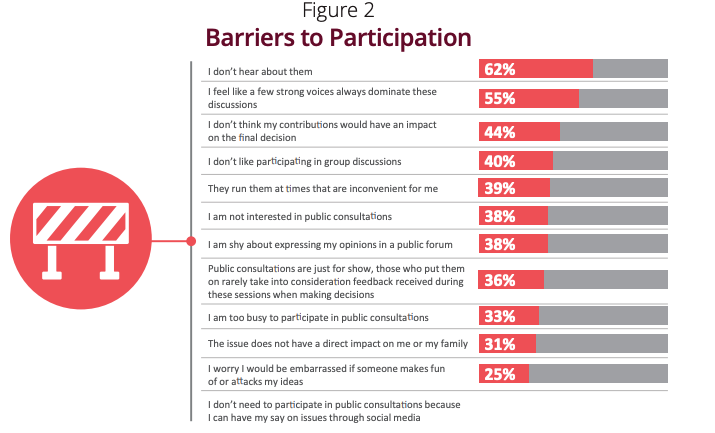

Only 20% of Canadians over the age of 18 reported they have ever participated in a municipal public consultation, with just 12 percent of these respondents saying they have done so in the past two years. Formal education and higher age brackets had marginally higher levels of participation, but engagement with municipal public consultations did not exceed 25% in any age bracket or demographic. Less than half (45%) of those who say they participated in a municipal public consultation in the past two years report attending an in-person open house, town hall meeting, or public engagement event. Further, the top two reasons why Canadians may choose not to participate in a municipal public consultation were that residents either do not hear about them (62%) or residents felt “a few strong voices always dominate these discussions” (55%).

The goal of public consultations is to engage citizens, promote dialogue between municipalities and their residents, share information, and solicit constructive feedback to guide future municipal decision making. Without feedback from residents, municipal decision making is not fully informed. COVID-19 has exacerbated dismally low public participation rates across Canada. As highlighted in a recent Windsor Law Centre for Cities report, reduced opportunities for meaningful participation in municipal governance during COVID-19 impact all residents, but the lack of voices representing the communities most affected by the pandemic is troubling. Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) communities are directly affected by, yet largely excluded from, some of the most important decisions being made by cities during the pandemic.

Many variables that have directly impacted BIPOC communities during COVID-19 stem from municipal decision-making, yet due to the structure of public consultations, these communities are often excluded from the conversation. As written in the report, “municipal state of emergency declarations and procedural changes have allowed cities to bypass processes needed to ensure responses benefit those disproportionately affected by the pandemic.”

With participation rates among residents dismally low and opportunities for participatory governance having declined during the pandemic, the question remains: how can we increase meaningful public participation in municipal consultations?

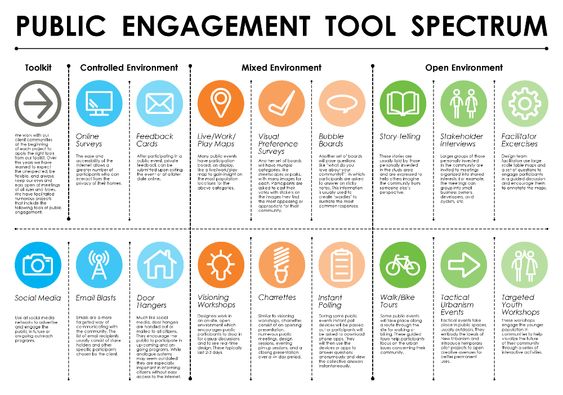

This question will be answered in subsequent blog posts in this series. However, the short answer is: municipalities need to deliver public consultation opportunities in a way that suits their residents best. As Princess Doe stated in a recent Windsor Law Centre for Cities blog post, municipalities need to meet residents where they are at. In today’s world, that likely does not involve a town hall meeting or even a separate online consultation for every planning issue that arises, but a process of ongoing engagement with a diverse group of residents about the municipal decisions that affect them, from land-use planning to bike lanes to climate policy.

Mallory Allan is a graduating Windsor Law student, and student member of the Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum policy clinic. We thank Jim Tischler, Visiting Fellow of the Windsor Law Centre for Cities, for acting as consultant to this blogpost series.

Main image credit: https://www.flyingkitemedia.com/devnews/philadelphiaschoolscharrette102914.aspx

Climate Blog series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 5

Concluding Thoughts: Lessons for Cities and Climate Action Planning Processes This post is the last of five in this series…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 4

Inclusive Climate Action through Charrette-Based Consultation This post is the fourth of five in this series written by Windsor Law…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 3

Public Engagement and Charrette Processes in Climate Action This post is the third of five in this series written by…

Climate Blog Series: Steps to Effective and Inclusive Public Engagement, Part 2

An Introduction to The Charrette Process This post is the second of five in this series written by Windsor Law…