Blog Series: Exploring the potential of Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs), Part 1

Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs): New By-laws, Potential and Challenges

This post is the first of a two-part series focussing on the potential of Additional Dwelling Units (ADU) to contribute to addressing Canada’s affordable housing crisis. This series appears in connection with the launch of the ADU data tool ADUSearch.ca. Part 1 defines ADUs, discusses developments in provincial and municipal policy frameworks across Canada to facilitate their construction, and raises both the potential and limitations of this form of housing design. Part 2 will explain the data tool, its applicability, and next steps for its roll-out across Canada. ADUsearch.ca received funding from the Housing Supply Challenge – Data Driven Round (Incubation Stage), however, the views expressed are the personal views of the author and CMHC accepts no responsibility for them.

(18 January 2022) by Shereen Arcis

Since the postwar era, federal housing policy in Canada has been defined by the promotion of private homeownership and the adoption of programs that are designed to attract private financial institutions engaged in mortgage underwriting for homebuyers. Critics maintain that the consequence of private homeownership remaining at the cornerstone of the federal government’s housing policies is that it continues to be subsidized “at the expense of much-needed policy support for other forms of housing.” As more and more Canadians are priced out of entry into the “traditional” home-ownership market, the impacts of these policy preferences have become more apparent.

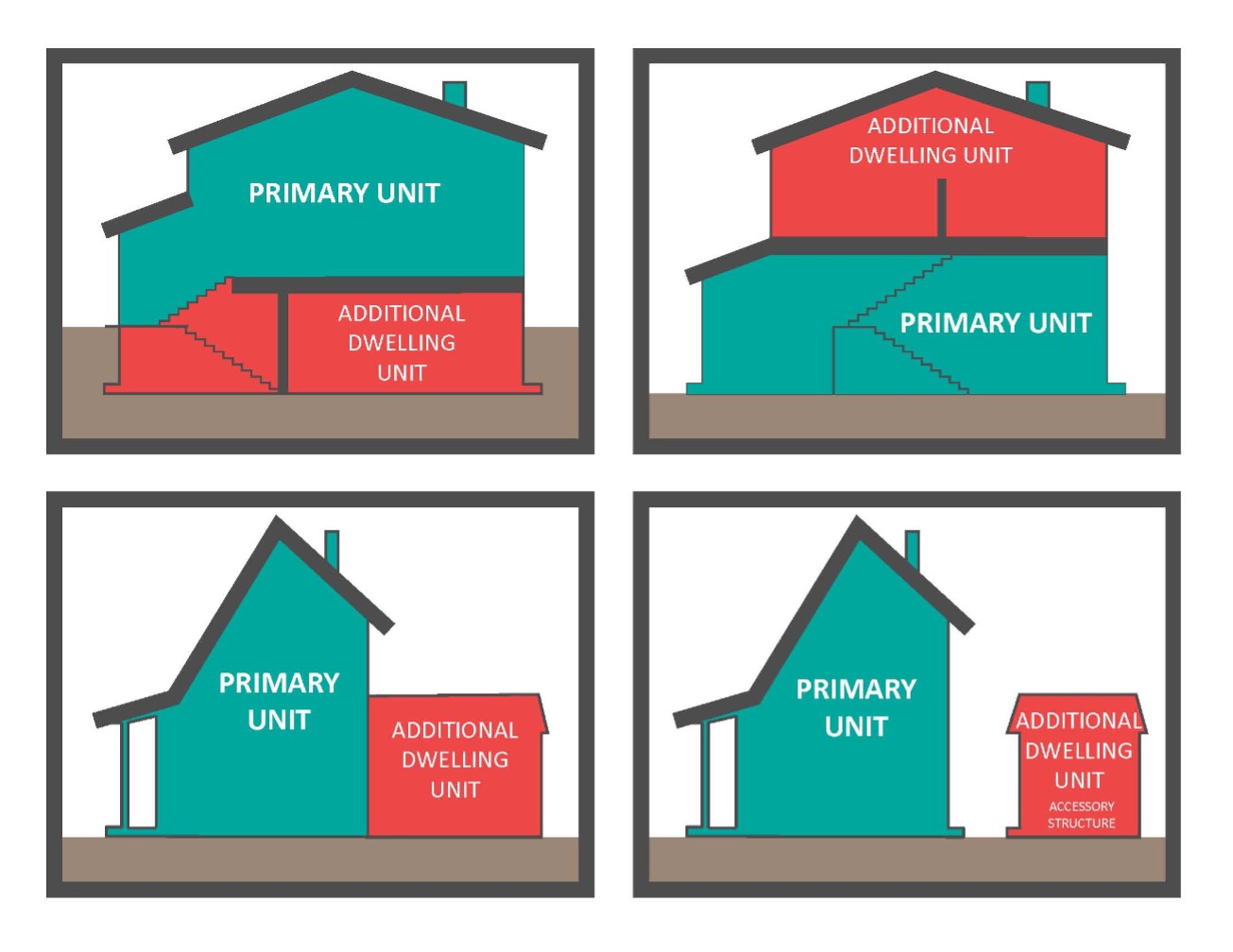

Given this reality, municipalities have sought to find ways to address these shortcomings through their own local policies, often with provincial support. One form of alternative housing supply that has been gaining support in recent decades is additional dwelling units (“ADUs”), which are “self-contained residential units with kitchen and bathroom facilities within dwellings or within accessory structures.”

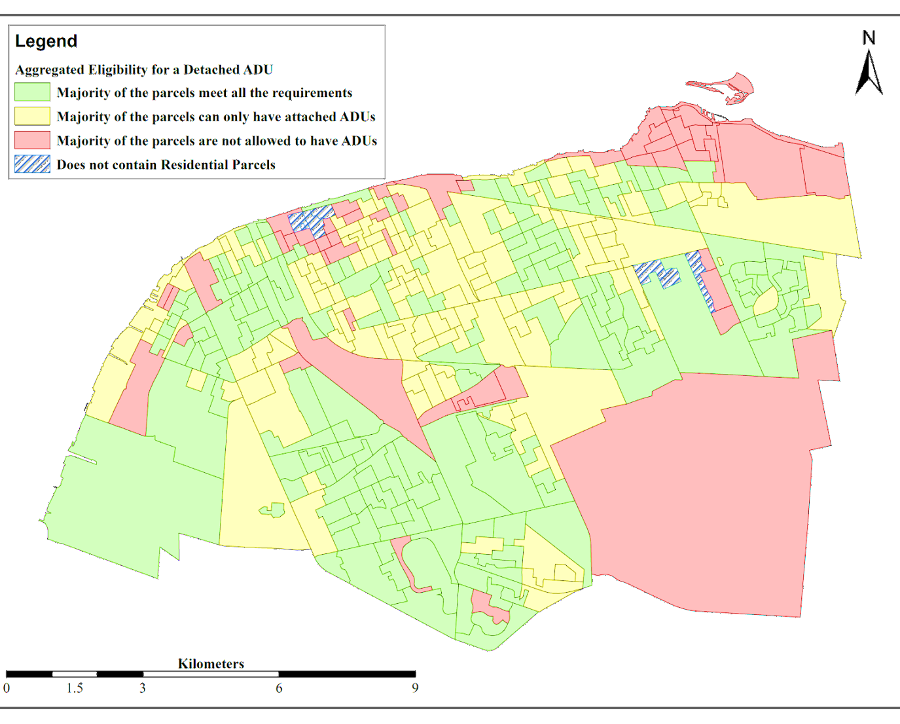

In Ontario, municipalities are mandated by provincial law to allow this alternative form of housing as a result of a May 2011 amendment to the Planning Act. Sections 16(3) and 35(1) now require municipalities to authorize ADUs in their official plans and zoning by-laws. However, each municipality in the province has the ability to decide how to regulate ADUs through their own zoning regulations. In the City of Windsor, the relevant zoning provisions can be found in section 5.99.80.1 of Zoning By-law 8600, which came into effect in June 2020 and provides guidelines for building height, floor area, municipal services, parking spaces, and setbacks. To date, other Ontario municipalities that have passed ADU by-laws include London, Kitchener, Guelph, Cambridge, Burlington, Toronto, Barrie, Kingston, Ottawa, and Sudbury. A noteworthy variable in these by-laws is the number of units allowed per lot. In accordance with the Planning Act, municipalities may permit a maximum of two ADUs per property—one within the main dwelling and one within an accessory structure. How a municipality addresses this and other questions may affect how impactful its by-law will be in supporting extensive ADU construction.

Evidence from Vancouver suggests that relaxing the requirements included in previous by-laws, such as by allowing the existence of one ADU per house in nearly all areas that were previously zoned for single-family dwellings, made it easier for homeowners to build conforming units, which has contributed to their undeniable success in the municipality. Indeed, Vancouver’s zoning framework is now conducive to the creation of ADUs, and it has become a leading city in North America when it comes to ADU development. The City of Vancouver’s success with this alternative form of housing has resulted in the municipality reaping the many benefits associated with ADUs, namely helping to address the lack of affordable housing. The benefits of ADUs to affordable housing are two-fold: on the one hand, ADUs boost the number of housing development opportunities, which has the potential to increase the supply of affordable housing without promoting urban sprawl. (ADUs have been recognized for their advancement of environmental sustainability, since they are built on existing developed land in established neighbourhoods and are low in square footage.) On the other hand, ADUs act as “mortgage helpers” that make homeownership more affordable by virtue of the rental income that is generated by these units.

Likewise, ADUs have become an attractive multigenerational housing option. Most notable in this regard is the degree to which these units offer opportunities to integrate and serve multiple generations and, as a practical co-habitation option, how they “enable people of all ages to live together and share space in different ways.” Furthermore, the concept of aging in place is specifically relevant, as ADUs allow seniors to grow old without moving to bigger scale or institutional settings. For seniors who are homeowners, having an ADU may also assist in overcoming the costs associated with home maintenance, which is a significant barrier to aging in place, because they help supplement senior homeowners’ incomes. The pertinence of this issue was underscored in the Liberal Party of Canada’s 2021 federal election platform, which included a commitment to “introduce a new Multigenerational Home Renovation tax credit to help families add a secondary unit to their home.” Politics aside, this election promise illustrates the growing relevance of ADUs in Canada’s housing policy.

Nevertheless, the rise in popularity of ADUs has not come with unqualified support. While the development of ADUs has been seen as a form of gentle densification, it can still lead to environmental concerns, namely when densification occurs in neighbourhoods that are already dense and have limited green space. ADUs may provide fewer units of housing for the space taken up than other larger-scale housing developments.

Similarly, if zoning by-laws only permit the construction of these units in certain areas with specific types of housing, they may lead to selective densification with building happening in some neighbourhoods, while others remain largely unchanged. This raises serious issues in regard to socio-spatial inequality. While it has been suggested that ADUs help address socio-spatial polarization by encouraging housing tenure mix, evidence from Calgary has shown the opposite can also be true: strong resistance to these units from homeowners has excluded non-homeowners and renters from many areas with single-detached dwellings. This, it is argued, has exacerbated socio-spatial inequality in the municipality, as ADUs tend to be concentrated in immigrant and low-income neighbourhoods.

Municipal governments should ensure that they take these factors, as well as many others, into account when adopting ADU by-laws. In particular, the pros and cons of ADUs should be carefully assessed and weighed within the context of each municipality and its broader plan to increase the supply of affordable housing, in an effort to craft thoughtful, place-specific housing solutions.

Lastly, regulatory barriers remain to the efficient design, approval and construction of ADUs in many municipalities. Complex approvals processes in particular have proven a disincentive to homeowners to engage in the construction of ADUs on their properties even when the by-law permits it. A November 2021 City of Toronto report notes that only 238 applications had been received in the three years since its by-law amendments to support laneway suite came into force, and the majority of these have not resulted in an actual build, seemingly in part due to delays in building permit issuance and minor variance application processing.

Overall, the vast potential of ADUs has become increasingly apparent, and some of that potential is already being realized in Canadian municipalities. Indeed, ADUs may constitute a sustainable approach to help tackle affordable housing, environmental concerns, and an aging population—some of the most pressing issues that are faced by municipalities today.

Shereen Arcis is a 2L Windsor Law student and a research assistant of the Centre for Cities, and during the summer of 2021 was a research assistant to the ADUsearch.ca project.

In addition to CMHC funding, adusearch.ca was made possible through the support of Family Services Windsor-Essex, the Centre for Cities (University of Windsor Faculty of Law), and the Cross-Border Institute (University of Windsor). More details about the project are available here.

Main image credit: AccessoryDwellings.org

ADU in the News

Blog Series: Exploring the potential of Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs), Part 2

A new online tool for affordable housing development: ADUSearch.ca (8 February 2022) By Sarah Cipkar & Shereen Arcis This post…

WINDSOR STAR: Centre for Cities-Supported Housing Data Project Receives $2.2 Million Federal Funding

(11 January 2022) Windsor-based housing project, led by Family Services Windsor-Essex and researchers Sarah Cipkar and Frazier Fathers, receive $2.2…

Daily News: Centre for Cities, Cross Border Institute Supporting Community Partners on Federally Funded Housing Data Research

(21 January 2022) The Windsor Law Daily News highlights the Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs) project, led by Sarah Cipkar and…

AM800: Housing Innovation and the Additional Dwelling Unit (ADU) Data Project with Frazier Fathers and Shereen Arcis

(January 19 2022) ADUsearch.ca co-lead, Frazier Fathers and Centre for Cities student researcher Shereen Arcis, talk with Dan MacDonald additional…

Blog Series: Exploring the potential of Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs), Part 1

Additional Dwelling Units (ADUs): New By-laws, Potential and Challenges This post is the first of a two-part series focussing on…