Climate Blog: Reframing our Objectives – The Importance of a Race-Centred Intersectional Approach to Environmental Justice

(23 March 2021) By Aucha Stewart.

Municipalities produce or have regulatory jurisdiction over approximately 50% of carbon emissions in Canada. As a result, they are at the forefront of addressing climate change. The approach municipalities take to address climate change concerns now will have a significant impact on environmental matters for generations to come. These decisions will determine if future generations will have the basic necessities of life such as clean air, water, and suitable soil. Applying an intersectional, race-centered approach to climate action and environmental justice allows municipalities to acknowledge historical disadvantages, the role these play in society today, and how the intersections of multiple variables negatively influence some individuals more than others.

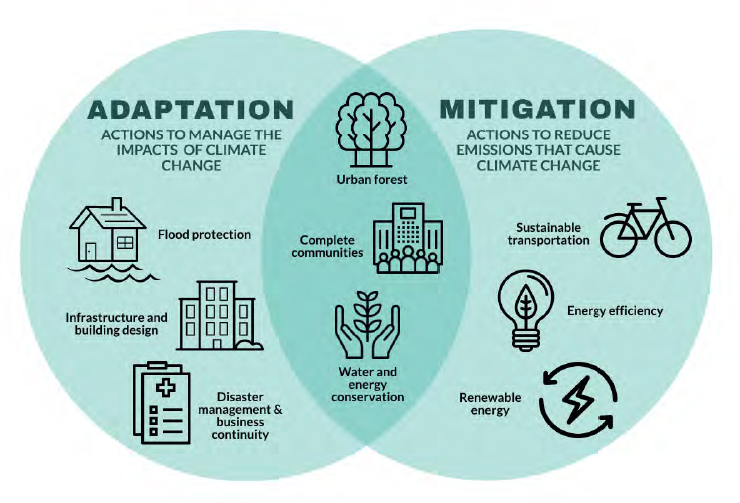

On November 18, 2019, City Council approved the Windsor Essex County Environment Committee’s motion that the City of Windsor pass a Climate Change Emergency Declaration. The Emergency Declaration noted that City Council aims to acknowledge Windsor and the County of Essex’s climate future as a high priority and take steps towards addressing the climate crisis. Significant strides still need to be made to adequately address the underlying issues that are and have been present in the City of Windsor. As mentioned in the administration report on accelerating climate action that went to Windsor City Council on May 4, 2020, a substantial focus must be placed on both adaptation and mitigation if we are to reduce emissions and adapt to projected climate risks. However in the Windsor City Council annual budget, passed on Monday, February 22, 2021, minimal new funding was allocated for mitigation and adaptation.

Does Climate Change Affect Us All Equally?

Municipal inaction with regard to climate action is most detrimental to vulnerable and minority populations. As Gochfeld and Burger highlight, “environmental risks are not uniformly distributed across groups of people. Minority groups and vulnerable populations are at a disproportionally high risk for environmental disease.” Independent of climate change and its derivative environmental racism, Black and Indigenous groups have dealt with structural inequalities for generations. The reason for this stems back to colonization and the systemic oppression and structural inequalities it created. Generations of inequality have left Black and Indigenous communities at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder. Consequently, when met with the disadvantages our current climate crisis presents, these marginalized communities are not adequately equipped with the necessary resources or finances to cope, relocate or adjust.

Lax and uninformed regulatory measures from municipalities reinforce social inequalities and can manifest in the form of environmental racism. Unfortunately, we do not have to look far to see a manifestation of governmental inaction resulting in environmental disease. Sarnia’s Chemical Valley has had deep effects on the Aamjiwnaang and Walpole Island First Nations. Our neighbours in Nova Scotia, too, can attest to this through their experiences of environmental racism and the detrimental effects it has had on vulnerable racialized communities. Exposure to toxic waste and air pollutants has resulted in increased asthma, cancer, and death rates.

In Windsor, despite longstanding concerns over the health impacts of industrial activity, there has been limited focus on environmental racism. Fortunately, efforts are being made to illuminate the experiences of Windsor locals. Platforms such as an upcoming ArtCite Waawiiyatanong residency are providing opportunities for community members to express their experiences of environmental racism. Windsor Law student Princess Doe writes about the proximity of the Ambassador Bridge – known to produce higher levels of cancer in its workers – to Sandwich, the neighbourhood with one of the highest concentrations of Black residents in the city.

Q: How can we ensure that municipal action regarding climate will improve the lives of vulnerable and marginalize populations?

A: “The quality of the solution you generate is in direct proportion to your ability to identify the problem you hope to solve” – Albert Einstein

The lens through which municipalities view climate change and its detrimental effects on vulnerable populations will determine how effective the solution will be. Environmental justice has been a topic of conversation in recent years and has often been used to combat the disadvantages minority groups continuously face. It has sometimes been defined as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. This framework, though a step in the right direction, is ultimately problematic as it does not truly address the underlying factors associated with the root issues faced by these groups.

The social and structural determinants of health of racialized communities are deep-rooted in a history of systemic discrimination. Without acknowledging (or being informed about) the history of the oppressed, government agencies and environmental organizations are likely to make decisions that negatively affect vulnerable and marginalized groups.

As Dr. Ingrid Waldron has stated, it is essential that policymakers, environmental organizations, and others addressing social justice struggles acknowledge the central role racism plays through the enduring impacts of colonialism and capitalism on the structures, lands, and the bodies of Indigenous and Black communities. Private members Bill C-230, being voted on in the House of Commons today, proposes a national strategy that allows the federal government to equip themselves with the data necessary to address the issue of environmental racism. Social and historical context education is critical for decision-making as it reduces the likelihood that racial inequities are being perpetuated systematically. Unconscious bias, lack of awareness, and inaction all produce results that are detrimental to marginalized and vulnerable populations.

What can be done to create change?

- Applying a race-centred intersectional approach to environmental justice. The way we view the issue determines the solution we provide. Failure to acknowledge the historical disadvantages Black and Indigenous populations experience will continuously result in plans and policies that miss the mark and disadvantage these groups.

- Addressing and budgeting for responses to climate change must be at the forefront of municipal decisions. Minority groups and vulnerable populations are often the first to experience the effects of climate change and the least equipped to adapt. Failure to adapt and mitigate the effects of climate change will disproportionately impact Black and Indigenous communities.

- Connecting with members of the community as a mandatory aspect of decision-making. Complex issues of climate change and environmental racism require collaborative organization and intersectional activism to bring about a better and more inhabitable future. Thus, it is necessary that municipal decision-making processes be inclusive of the local residents that will be directly impacted. There is value in a variety of perspectives.

The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members.” -Gandhi.

Canada as a whole has made significant steps in the right direction with regard to climate action. But this does not mean there is no room for improvement. We are not truly advancing as a society until we address the health and security of our most vulnerable members. While we are progressing towards a better future, I challenge you – whether municipal decision-maker or community member – to adopt a race-centered environmental justice approach and understand that race, socio-economic status, gender, and countless variables intersect and influence the quality of life for many. On a municipal level, this understanding is crucial and should be used when budgeting for climate action and making urban planning decisions.

Aucha Stewart is a 2L Windsor Law JD student and a member of the Windsor Law Cities and Climate Action Forum (CCAF).

Opinions expressed in blog posts are those of the author and do not reflect an official position of the Windsor Law Centre for Cities or CCAF.

Main image credit: Shutterstock. Factory and residential neighbourhood in Hamilton, Ontario