Guest Blog: Take the students outside this school year, especially in our cities

(17 September 2020) By Josh Fullan [cross-posted with Spacing.ca]

With school resuming, the most important message many Canadian students can hear right now might not have anything directly to do with the coronavirus or filling the learning gap.

That message is: go outside, and be active.

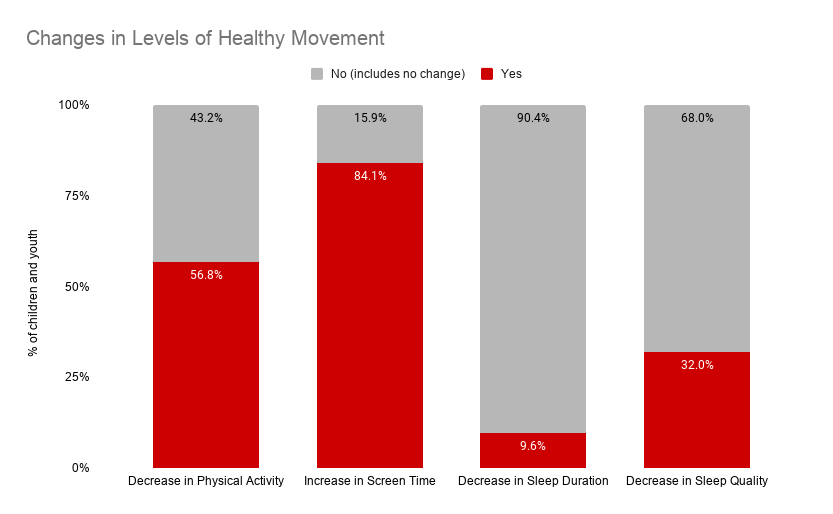

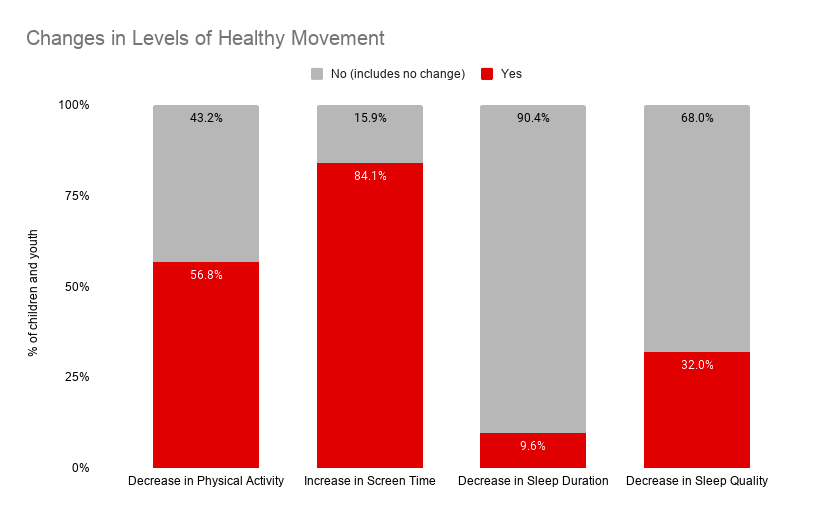

Several recent studies confirm an alarming health trend for kids and teens who have been living through pandemic conditions that, to varying degrees, included mobility restrictions, remote learning, park and playground closures, and quarantine. So it is perhaps unsurprising that the majority of Canadian children and youth report being less physically active during COVID-19.

In the spring and summer of 2020, Maximum City conducted parallel Canada-wide and Toronto-based surveys of the impacts of COVID-19-related social and physical distancing on the self-reported behaviours, school experiences, and feelings of children (ages 9 to 12) and youth (13 to 15) in 932 households across Canada. What is unique about this study is that it directly captured the experiences of kids and teens rather than have a parent or guardian report these behaviours and feelings on their behalf. Respondents were selected from an online panel to closely align with household income levels, racial backgrounds, and provincial population distribution across Canada.

(Source: Maximum City with Dr. Raktim Mitra, Ryerson University)

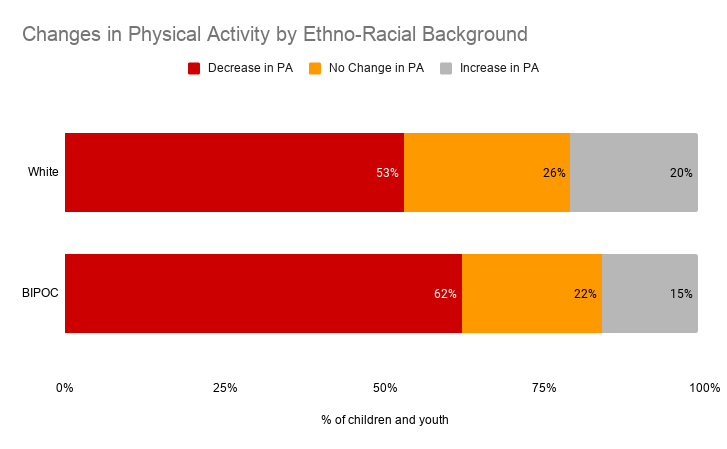

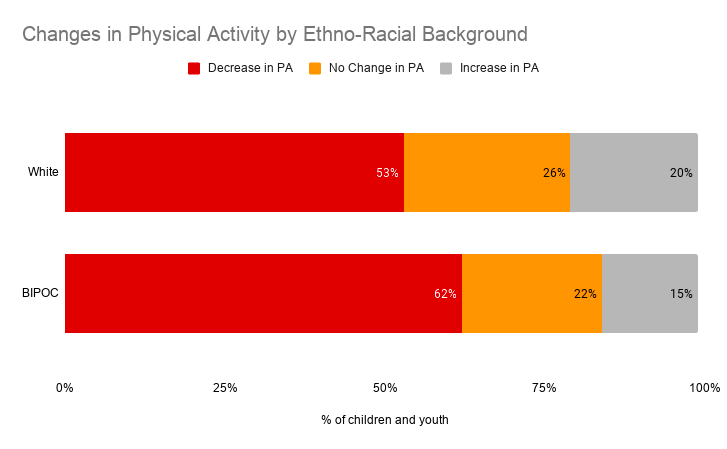

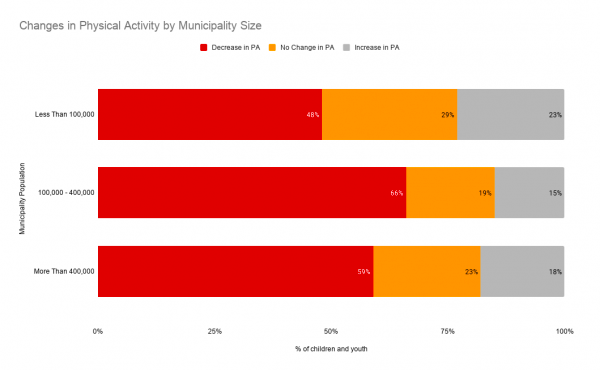

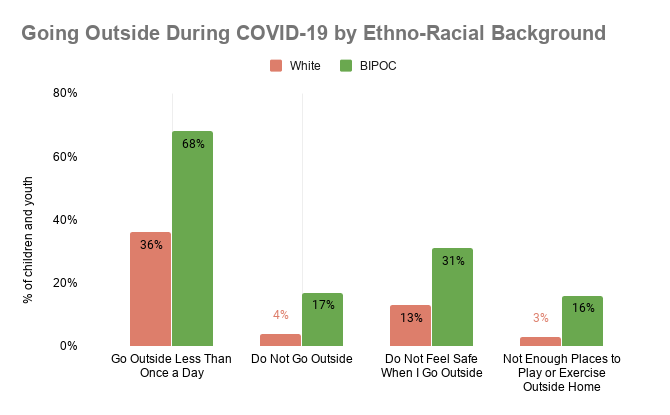

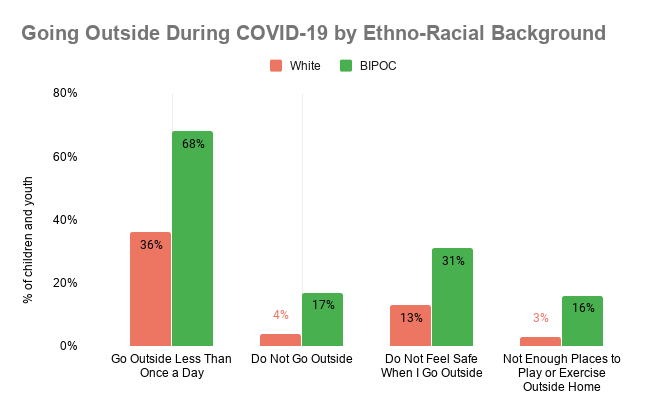

As with the transmission of the virus, there are spatial and racial inequalities in the reported levels of healthy behaviors. Black, Indigenous and children or youth of colour, as well as those who live in medium and larger cities, were more likely to report a decrease in physical activity during the pandemic.

Source: Maximum City

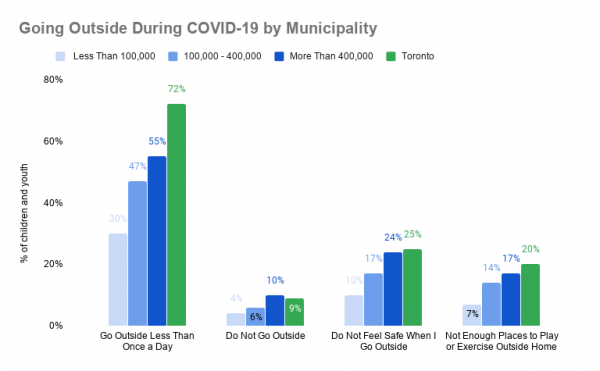

In terms of the infrequency of going outside, the trend was similarly exacerbated when applying race and place as variables. Nearly half of Canadian children and youth reported going outside less than once a day during the pandemic, while more than two-thirds of BIPOC kids reported going outside less than once a day. They also reported having fewer places to play and feeling less safe outside. For those in large cities, and particularly Toronto, these numbers are shocking and represent a call-to-action for policy-makers, planners, and the municipal public health units who have done such good work tackling the virus itself.

Source: Maximum City

Low levels of physical and/or outdoor activity are linked to poor health and well-being outcomes for children and youth. The Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth recommend at least one hour of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and several hours of a variety of structured and unstructured light physical activities, each day. A 2020 UNICEF study of child well-being found strong links between the frequency of playing outside and children’s happiness (and ranked Canada 30th of 38 rich countries in child well-being outcomes. As UNICEF Canada President David Morley noted at the study’s launch, this is not a report card any Canadian will be hanging on their fridge to show off).

The evidence shows clearly that many Canadian kids have not been meeting those guidelines during COVID-19.

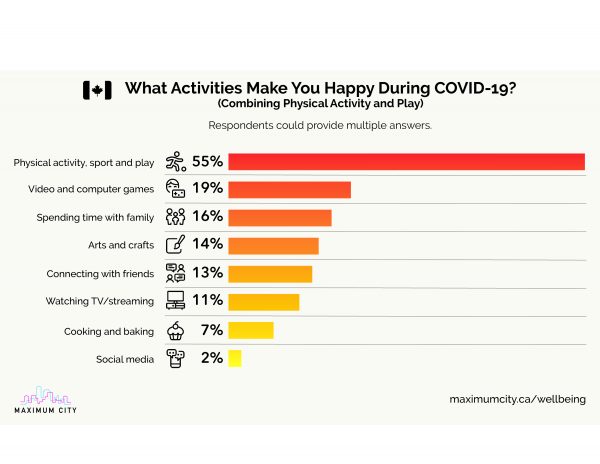

When we listen to kids, they say that physical activity and play are what have made them happiest during the pandemic.

Notable in the UNICEF report is that Canada ranks in the top third of rich countries for educational outcomes, but in the bottom third for mental well-being and physical health. Our strong education system is being seriously threatened in some provinces; defending it is one of our greatest collective responsibilities as a society during the recovery, along with keeping transmission rates low. For many kids, engaging deeply with school is a major part of their well-being that has been compromised by ad hoc remote learning and low levels of social interaction.

As parents, teachers, and residents of one the most urban and diverse countries in the world, we must not ignore the uneven impact of the pandemic on urban and racialized kids. The most useful recovery solutions will not be one-size-fits-all, but rather focus on the greatest deficits.

And if a second wave locks us down again, decision-makers must think hard about consequences and alternatives before closing parks and playgrounds in our urban communities. In the interim, as we brace ourselves through the anxiety of return-to-work and incoherence of back-to-school plans, a simple directive that will benefit all children and youth should be top-of-mind with parents, caregivers, educators: Go outside. Be active.

Josh Fullan is a teacher and founder of Maximum City, an education and engagement company in Toronto. Follow Josh on Twitter at @joshfullan. He may be reached at [email protected].