Contextualizing Anti-Blackness in the City

(4 November 2020) By Princess Doe.

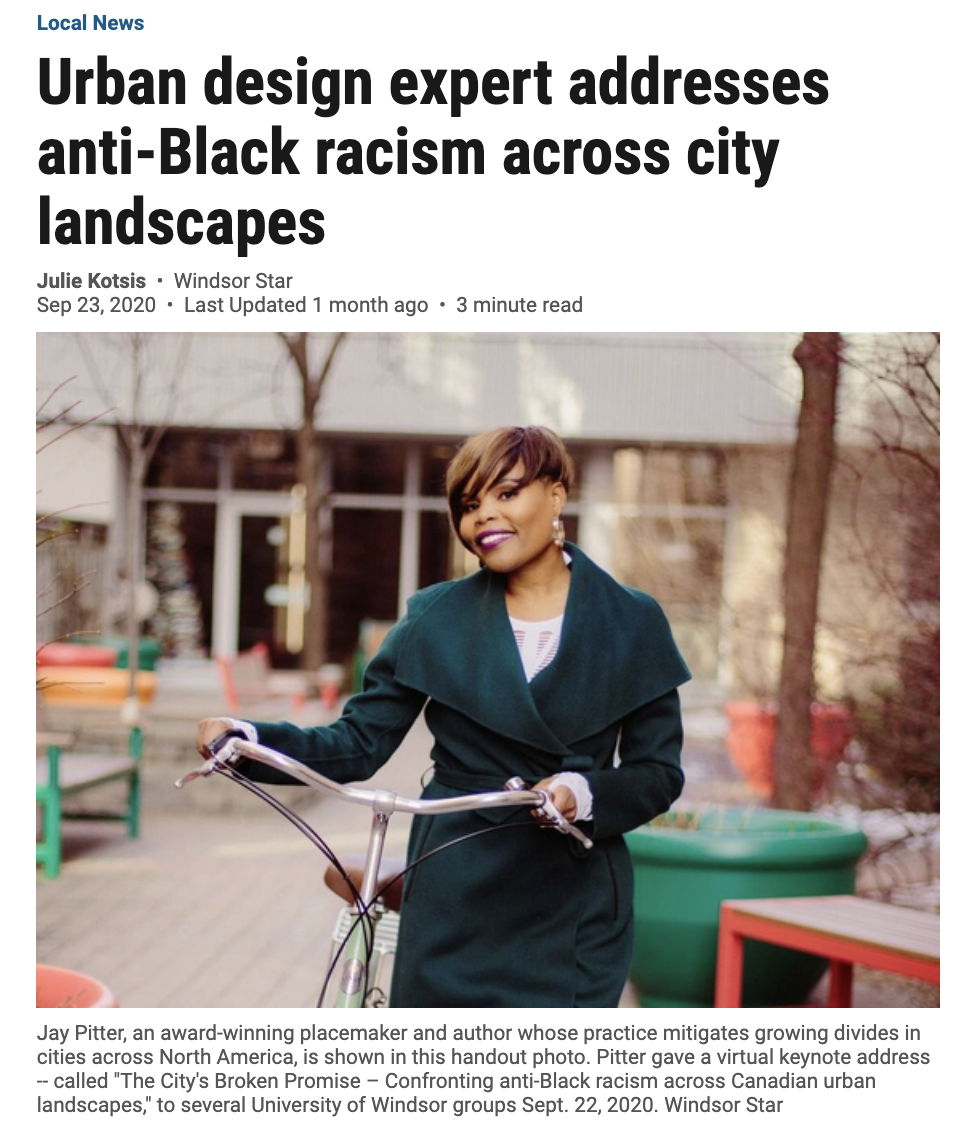

The introduction of Black bodies in public spaces was on the auction block. The auction block refers to Black people who were forced into slavery being presented to White owners “for purchase”, subjected to violence and sexual exploitation. And as award-winning placemaker and author, Jay Pitter, contextualized in her recent public keynote in Windsor, The City’s Broken Promise: Confronting anti-Black racism across Canadian urban landscapes, this initiation of anti-Blackness has engendered a legacy of continued systemic and institutionalized discrimination of our Black communities in present day.

The global Black Lives Matter movement and calls for racial justice have been focused on solidarity with African-Americans, particularly as it relates to police brutality. However, with the police killings of Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (“BIPOC”) in Canada over this past year, and data showing that Black communities are dying at disproportionate rates from COVID-19, it’s evident that several areas where inequities are deepest are local in nature, such as policing, health, and housing.

In the public keynote and follow-up workshop with community leaders, Pitter looked to historically spatialize anti-Black racism in Canadian cities, with the keynote serving as a medium to deconstruct the persistent Canadian myth that multiculturalism equates to equity and inclusion. Windsor, particularly with its unique positionality as a border city for Detroit (a city of great significance to African-American history and culture) could arguably be viewed as a microcosm for how enabling this mythology can lead to leaders and decision-makers ignoring how they are exacerbating anti-Black racism.

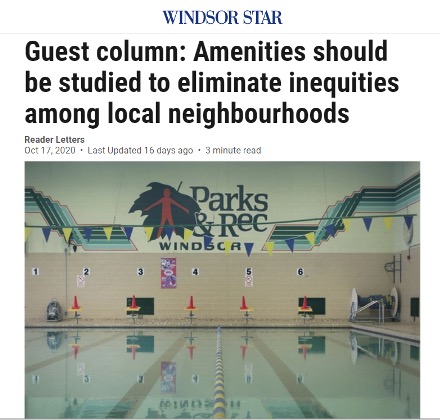

Pitter’s lecture highlighted for participants how explicit racist by-laws and practices of yesteryear may take on more subtle forms today but have the continued effect of disenfranchisement. For example, active urban segregation practices that historically limited the number of swimming pools in predominately Black neighborhoods have been correlated with higher rates of drownings in Black populations. As Sarah Mushtaq notes in her recent Windsor Star column, Black children in the United States aged 5-19 drown at a rate 5 times than that of their white counterparts, according to the Center for Disease Control.

A similar effect is seen with the development of car-centric infrastructure, which benefited predominately white affluent families in the early 19th century. The car provided freedom for white families to leave for suburban neighborhoods. In many cities, this led to a lack of transit infrastructure for urban centres, which tend to have a higher density of Black populations. Access to amenities and implications of transit infrastructure and how it impacts BIPOC and low-income communities, who are more likely to be users of transit in car-centric cities, are brought into question.

In Windsor, this point has been highlighted by those critiquing the proposed location for a new mega-hospital. The plan, which would close both acute-care hospitals in existing Windsor neighbourhoods and locate the new one more than 12 km from the neighbourhood with the highest per capita Black population in the city, also lacks a viable transit access plan, further limiting access to health services for these communities.

As Pitter notes, there never may be a truly safe space for marginalized communities. However, if there was one overall lesson to be taken away from the public keynote and the workshop it is that in seeking to develop a city that incorporates everyone, it is essential to connect all place-based decisions and planning to Black issues through an intersectional lens. Pitter set out 5 key ideas:

1. Acknowledge the auction block

Anti-Blackness permeates all spaces, as the very introduction of Black bodies in public space on the lands in what we now call North America was on the auction block. Ongoing public consultation with the Black community in developing both public and semi-public spaces (such as restaurants, cafes, and libraries) aims to dismantle the legacy of the auction block.

2. Interrogate and amend anti-vagrancy laws

Anti-vagrancy laws, that were used historically to target predominately Black individuals, are today the basis for racial profiling, carding, stop and frisk, and fines for transit violations, failing to provide community safety for Black communities. The legacy of anti-vagrancy laws lies in expanding policing powers that disproportionately leads to police brutality towards Black and Indigenous populations.

3. Address citizen profiling in the planning and use of public spaces

Black communities are citizens and users of public spaces. It is important for the wider community and those in positions of power to acknowledge that, and to address how they react to Black bodies in these spaces. For example, Black boys on a basketball court are often treated as a threat compared to white boys playing tennis.

4. Transition from public space ownership to public space stewardship

We must look beyond merely protecting public spaces, and encourage the use of public space that involves and led by all members of our community. Parks where public spaces historically designed for affluent (white) families. Over time, it is clear that they have become safer spaces for historically marginalized communities such as sex workers and queer men who did not have any other safe space to meet. The implications of public spaces and “ownerships” has been evident with groups advocating for the protection of tent encampments.

5. Understand and embrace the alchemy of public space production

Public space is never neutral; an equity lens is needed when we are planning communities, and considering unique impacts on Black communities. In Windsor, identifying knowledge gaps, and developing more knowledge-building and resource guidance for the community in connecting anti-Blackness to place-based issues, is essential for moving from conversation to action. One intervention that has been used to address this elsewhere is the City of Toronto’s creation of a Confronting anti-Black Racism Unit.

As we look to cities to take the lead on an equitable recovery from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it is even more urgent that their responses include acknowledging and addressing their role in anti-Black racism, and involve Black voices in the decision process. This is critical if there is to be a true just recovery for all.

Princess Doe is a Windsor Law student and Student Research Associate for the Centre for Cities. She is also co-Chair of Making it Awkward: Challenging Anti-Black Racism, which was a co-organizer of the Jay Pitter event.

Opinions expressed in blog posts are those of the author(s).

Cover photo by Princess Doe, taken in Ford City, Windsor.