Guest Blog: Climate justice is racial justice

(17 July 2020) By Aisha Poitevien, Development Officer, David Suzuki Foundation

(The following are the views of the author and not necessarily her employer)

The recent protests in the United States following the wrongful death of African Americans like Goerge Floyd and Breonna Taylor have sparked outrage across the world. Here in Canada, the deaths of Toronto’s Regis Korchinski-Paquet and Chantel Moore from Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations in British Columbia — while in police custody — remind us that we too have a history of police brutality.

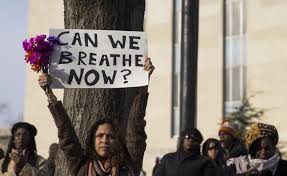

Protests have broken out across the country from Toronto to Windsor to Vancouver to fight for Black Lives and for a change in the current police dynamics, especially with regard to dealing with BIPOC communities. While attending the protests for BLM in Ottawa, I was reminded of the Wet’suwet’en” and Climate Strike protests I had recently attended, and it highlighted how these movements are linked: how fighting for climate justice is also fighting for social justice.

Many institutions in our society like healthcare, education, and financial institutions continue to place BIPOC people at a disadvantage, and these can be worsened by climate change. One of these ways is air pollution. A report published by Stats Canada in 2017 showed that new immigrants in Canada tend to breathe more polluted air compared to white Canadians. The study looked at a city such as the GTA, where many newcomers and immigrant groups live, and found that compared to White Canadians living in large cities, newcomers, immigrants and those of lower social-economic backgrounds are inhaling more toxic particles.

When George Floyd and Eric Garner said “I can’t breathe” before passing away due to oxidation at the hands of police, for me it also highlighted the systems that make it harder for us to breathe. Black people are also more likely to suffer from respiratory illness. Although it’s hard to find exact percentages in Canada, Black people across the world are genetically predisposed to suffer from a respiratory illness like asthma. In the United States, according to the Asthma and Allergies Association of America, African Americans and Hispanics have the largest rates of asthma in the country. Not only are African Americans more likely to have asthma, but their condition also tends to be more severe, and less reactive to treatment. In Canada, Indigenous youth have a 10% chance of having asthma, making it the second most common chronic illness in this section of the Canadian population.

In a time where a global pandemic that affects the respiratory system, and disproportionately targets African Americans in the United States, exposure to poorer air quality could exasperate the outcomes of succumbing to the illness. Although in Canada we do not collect enough race related health data to know the impact of Covid-19 on ethnic communities, we know it’s more prevalent in Black communities in Toronto. How ironic is it then that the autopsy for George Floyd showed that he was also affected by Covid-19? People of colour are often powerless to the systemic racism that surrounds us. When environmentalists are fighting for better air quality, they should make sure to outline how it affects people of colour more, and how these communities will benefit the most from breathing fresh air. The reality is that right now, many of us can’t breathe.

Like air pollution, water is a natural resource that contributes to systemic differences by race in Canada. This is particularly true in 61 Indigenous communities where drinking water advisories are currently in place. The Neskantaga First Nation in northwestern Ontario hasn’t had access to safe tap water since 1995. Last August, Indigenous Canadian activist Autumn Pelleter shared on her Instagram a picture showing “Canadian Water vs Indigenous Water”. One was clear (and what most of us get when we open our taps in Canada), while the other was dark brown. As Canadians, we often think of unsafe drinking water as a third world issue. For me, living in a large Canadian city, I have always been able to open my tap and drink safe water that wouldn’t poison me.

In her book “There’s something in the Water” Dalhousie University Professor Ingrid R. G. Waldron looks at how populated water has affected Black and Indigenous populations for generations. She also looks at other environmental factors that have affected the Black community in Nova Scotia since their arrival in Canada in the 1800s. One obvious example is Africville, a Black Canadian community that was deprived of basic services such as access to clean water, sewage, and waste management. Africville’s proximity to the development of an infectious disease hospital, a prison, and a garbage dump over time added to deplorable living conditions imposed by the City of Halifax. (The book has been made into a film, now available online,)

Environmental racism is real. It determines whether or not you live near a waste plant, breathe polluted air, or drink contaminated water. For populations of colour, who also face increased health issues such as respiratory illnesses and many others, the combination of these factors can be deadly. It’s an issue Lenore Zann, a Member of Parliament from Nova Scotia, is hoping to bring to the federal government’s attention through a new bill. Bill C-230, also known as the National Strategy to Redress Environmental Racism Act, would create a national strategy to promote efforts across the country to redress the harm caused by environmental racism.

As we’re all watching protests for racial justice due to police brutality, we must be aware that many other factors are destroying ethnic communities. These factors are all related to the worsening effects of climate change on the planet. Fighting for cleaner air, safer water, and less toxic waste will benefit all of us, but will be life changing for BIPOC and communities of colour. When we’re fighting for environmental policies, we should make sure to include BIPOC and people of colour in mind. We also need to collect more scientific data on how climate change specifically affects vulnerable populations in Canada.

In the end, we are the ones most affected by the negative effects of climate change.

(Cover image: Rachel Joanis, racheljoanis.com)