Climate Blog: Municipalities can help mitigate climate change by prioritizing wooden structures

(13 April 2020) By Peter Dalglish (Windsor Law 3L student, Cities and Climate Action Forum member).

For many, the thought of wooden buildings can conjure up images of some of the great fires of history. In two short days, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed over 17,000 buildings and left 100,000 residents without homes. Detroit, before the discovery of the internal combustion engine and the assembly line, was a wooden frontier outpost that entirely burned down in the early 19th century. Fires leave an impressionable mark on cities. Detroit’s previous flag depicts two women from this period – one crying, expressing remorse and pain over the loss of their community, the other gesturing as if she is looking to the future towards an era of resurgence and optimism.

Photo Credits: Detroit Historical Society

It is worthy in this period of concern over our planet that we too look towards the future and consider what a wooden structure may offer in contemporary urban design and construction.

Attention is often given to municipal developments that seek to adapt to climate change, rather than mitigate it. Infrastructure like flood walls and pumping systems provides inhabitants with a better quality of life against rising sea levels and other implications of the changing climate. But adaption is only one part of the picture. Municipalities and municipal actors must take into consideration how design and construction of structures can mitigate climate change as well. One of these ways is through wooden structures.

Photo Credits: University of Toronto

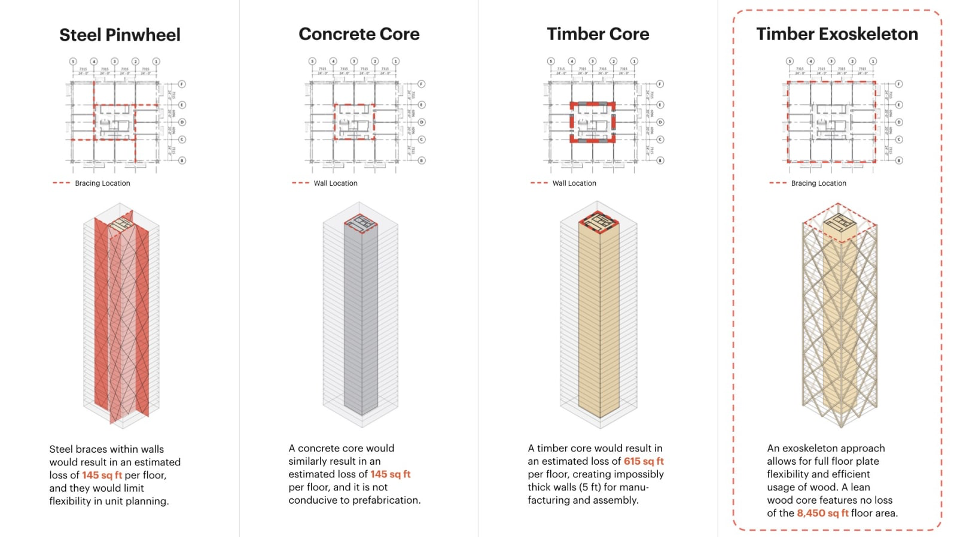

Construction is about to begin on a 14-storey, 80-metre tall tower on the University of Toronto campus in downtown Toronto. Built on an entirely wooden frame, the tower will be the tallest mass timber structure in North America. Removing the need for steel in constructing a building drastically reduces its carbon footprint. Vancouver’s Brock Commons tower, an 18-storey wooden structure that previously held the title of tallest timber building, offset over 2000 metric tons of carbon. That is approximately the same carbon footprint that an individual releases if they were to fly from New York to London 2000 times.

Steel is just one building component used in the construction of traditional multi-storey towers. In order to construct the core of a building, tonnes of concrete are required to be poured for the entire height of the high rise. According to British think tank Chatham House, concrete production and transportation are major contributors to global carbon dioxide emissions, compromising 8 per cent of global emissions.

Photo Credit: Sidewalk Labs

With the use of a timber exoskeleton like in the Toronto and Vancouver examples mentioned above, the need for steel and concrete is significantly reduced and less carbon is released into the atmosphere.

Timber provides an additional benefit as a building material through its ability to capture and store carbon. A study in the journal Nature Sustainability confirms that “carbon storage in mass-timber buildings will offset some of the temporary reductions of carbon stock in forests, which will re-grow and continue to absorb carbon from the atmosphere. This transfer of carbon from forests into cities may compensate for the weakening of the land-based carbon sinks as air temperatures rise and the frequency of natural disturbances relating to climate change that affect forests increases.” The cyclical process of trees absorbing carbon as they grow and using the wood in structures where they are effectively stored contributes to a reduction of carbon in the atmosphere. In an era where expansive and energy-intensive carbon-capture systems are being developed, considering storing carbon in wooden structures seems almost mundane. But returning to practices that were once common in past times – walking and using active transport before the car, eating seasonally and locally before importing food – are serious and practical ways of reducing our carbon footprint. For a progressive municipality to demonstrate action in meeting the climate emergency declared in over 400 Canadian municipalities, more wood and less steel and concrete should be used in building construction.

In order to encourage this, policymakers can take action through a variety of ways. Wooden structures require developers, architects, and construction firms to navigate around provincial building codes. In Ontario, timber structures over 6 storeys must apply for their building permit under the Alternative Solution pathway. While scrutiny should be applied to ensure all buildings are safe and sustainable, it may serve Ontario better to formalize a policy in the building code for granting permits to wooden structures, as opposed to directing builders to find alternative pathways.

Municipal policymakers can take action through inserting language into official plans that encourages the use of wood as a construction material. Official plans often contain a section devoted to development strategy. The City of Windsor is one example. The City of Windsor’s Official Plan includes a section on development strategy at Chapter 3 of Volume 1. Windsor City Council also passed a Community Energy Plan in 2017 that sets outs practical, long-term steps for the city to meet its environmental targets. No mention of wooden structures exists in the Plan, but with the passage of Windsor’s climate emergency declaration, perhaps more political will exists for this comprehensive Plan to include targets for building materials.

On February 19th, 2020, the City of Windsor’s Environment, Transportation and Public Safety Standing Committee unanimously supported seven “priority one mitigation Actions” put forward in the “Acceleration of Climate Change Actions” plan (the plan was to go before Windsor City Council on 23 March 2020; however the meeting was cancelled due to COVID-19). Rather than focusing on adaption, these Actions serve as tangible goals for the municipality to rely on in responding to city council’s decision to declare a climate emergency in 2019.

Two of the seven mitigation Actions will benefit from prioritizing the use of timber in construction: establishing a low-energy economic development area surrounding the Gordie Howe International Bridge, and creating a climate change strategy for the Sandwich South area – a possible net zero energy neighbourhood – for any significant development there. While these two Actions make reference to carbon neutrality, both development projects would benefit from explicit obligations on developers to use timber in the construction process. City council could implement these through Official Plan amendments or through zoning requirements for the two areas.