Blog: Green bonds – a catalyst for municipal action against climate change

(26 February 2020) By Sharath Voleti (Windsor Law 2L student, Cities and Climate Action Forum member).

Climate change is among the most serious threats facing humanity. According to the United Nations, the global rise in temperature must be kept within 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, or large swathes of the planet will become uninhabitable. Based upon current projections, the world has 12 years to prevent this outcome.

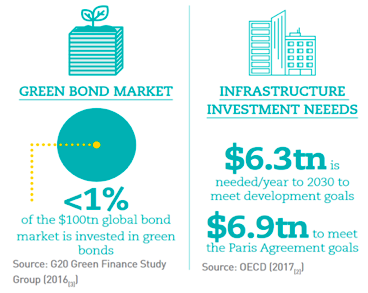

In response to this, the current federal government has issued ambitious goals such as making Canada carbon neutral by 2050, while municipalities such as Toronto are seeking to do the same by 2040. To meet these goals, a staggering amount of capital investment will need to be mobilized. It is estimated that countries worldwide will need to spend $6.9 trillion a year to meet their 2030 Paris Climate Accord (“Paris Agreement”) targets. The investment required to meet current and future goals makes clear that the public sector and private sector must work together as evidenced below.

Robust action against climate change must be led by the federal and provincial governments due to the scale of the challenge and Canada’s constitutional structure. However, this does not mean that municipalities do not have an important role to play. Such efforts require capital, which runs into the age-old problem of municipal fiscal capacity. Consequently, this blogpost will argue that green bonds are an effective catalyst for municipal action against climate change, and municipal fiscal incapacity.

Ontario Municipal Legislative Background

Every Ontario municipality except Toronto is governed by the Municipal Act, 2001 (the “Act”). Under section 394(1) of the Act, a municipality is prohibited from imposing an income or carbon tax on residents. Consequently, municipalities have traditionally raised revenues through property taxes, development charges and by-law enforcement.

Windsor

Such tools, however, are insufficient, and may not always be viable for smaller and less prosperous cities. Take the City of Windsor for instance. The City is located on flat land and surrounded by water on three sides, which makes it susceptible to flooding. This risk has been exacerbated by climate change in recent years. In 2016 and 2017, the city saw two once-in-a-century type storms within a 11-month period. The 2017 storm cost $175 million in damage, and flooded 6,116 homes. It is estimated that the city requires over $500 million to renovate and build sewer infrastructure to address the issue, but has been unable to secure the funding through existing financing tools or higher-order governments.

Green Bonds

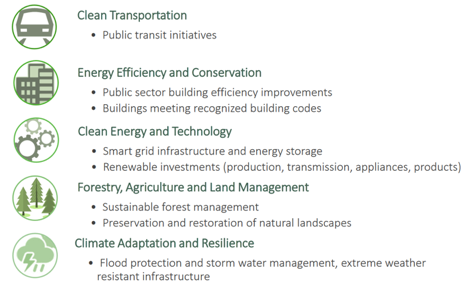

Under the Act, municipalities may raise revenues by accruing debt within reasonable limits. A green bond is a type of debenture sold on the market “whose proceeds are earmarked for environmental or climate-related projects, such as public transit.” Green bonds are structured like regular bonds, in the sense that investors are paid back their principal plus interest over time.

The first ever green bonds were issued by the European Investment Bank in 2007. Green bonds have experienced astronomical growth worldwide in recent years, with a 90% growth in 2016 and 87% growth rate in 2017. Their overall volume was projected to increase to between 180 to 250 billion by the end of 2019. Examples of projects funded include:

Green bonds in Canada

Canada is ranked as the world’s ninth largest issuer of green bonds globally, with all three levels of government having issued green bonds worth approximately $15.2 billion by the end of 2018. Municipalities issued 42% of Canadian green bonds issued in 2018, with Ottawa being the first Canadian municipality to issue a bond. Currently, the green bond market in Canada is rapidly expanding and characterized as “highly oversubscribed, suggesting a [positive] mismatch between current demand and available supply.” Given recent political developments in Ontario, it is notable that the current provincial government issued a $750 million bond to finance the Eglinton Crosstown LRT project and GO Transit expansion in November 2019. Indeed, Ontario is the largest issuer of green bonds, and has issued $4.75 billion worth since 2014 as evidenced below.

Due to their higher compliance and certification, green bonds receive preferential interest rates and other benefits. For instance, the City of Ottawa is estimated to have saved $400,000 in interest costs by issuing a green bond, when compared to a regular bond.

Green bonds however do have some disadvantages. To start with, green bonds are sold based on creditworthiness. If a municipality does not have a history of borrowing or does not appear or have the capacity to pay back borrowed funds, they will not be assessed to be credit worthy. In addition, the issuance of a green bond requires a sophisticated city administration framework that municipalities may not possess or have the resources to create.

While this blogpost has focused on the feasibility of green bonds, it should be noted that they may also be positively correlated with larger emission reductions. A recent econometric analysis by the World Bank found that a carbon tax (currently in place in Ontario) actually “improves the performance of green bonds, which in turn improve inter-generational equity, political feasibility, and help address multiple market failures.”

Why does debt accrual make sense?

Most municipalities are hesitant to accrue debt to finance projects, as it runs counter to prudent fiscal management. However, debt financing has been used by governments around the world since capital markets and financiers have existed. Debt financing is also attractive because interest rates are currently at record lows. In 2019, the City of Sudbury raised $205 million to fund projects by issuing debentures in part due to low interest rates. In February 2020, the Windsor Environment, Transportation and Public Safety Standing Committee examined the feasibility of green bonds when discussing a city administration report responding to the November 2019 climate emergency declaration.

The Government Finance Officers Association notes that it is “not fair to burden current taxpayers with the cost of assets people will use in the future.” To use a example, paying upfront for a road that is expected to last 20 years, means that everyone in subsequent years is essentially using the road for free.

The same logic arguably applies to using green bonds to finance projects combatting climate change, which will require sustained investment and policy action for decades. Any actions taken today will benefit future generations. Consequently, it makes sense that these costs be amortized and spread out by debentures like green bonds, given current legislative, fiscal and political realities.